THE SIXTY EURO PROBLEM

In stark contrast to their professed demands, Slovenians can be very ungrateful

when the foreigner tries to speak Slovene, which is initially mystifying.

Who among them is responsible for this?

Why are they in such a hurry to get off the subject?

Why don't they want to use their perfect English to correct learners when they err?

Why do they pounce within seconds on any mistake or hesitation in

beginners' attempts at Slovene, as an opportunity to demean or patronise?

Why do they prefer to clam up in response to questions about Slovene?

Why is it important for them, for the foreigner to fail?

Is contempt a constructive teaching method?

Is learning anything usually a competition between the teacher and pupil?

Is it really surprising who doesn't learn Slovene?

Here's the problem.

To a Slovenian acclimatised to the situation described, teaching Slovene to an

English speaker is a double negative.

To visualise what's wrong let's imagine a

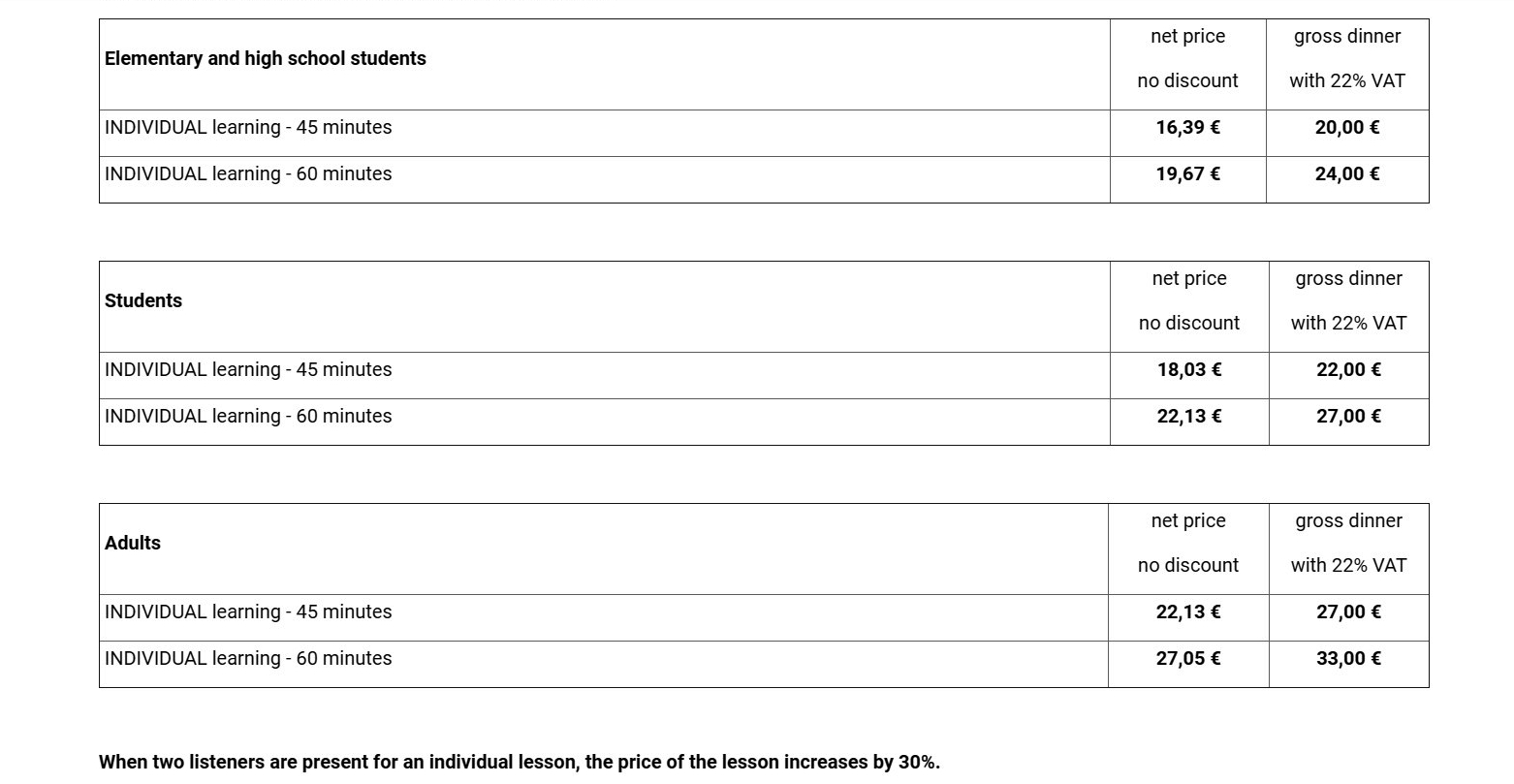

language school in a small Slovenian town offers conversational and corrective English, with grammar tips, and a range of subject matter or

disciplines upon which Slovenians could discuss the terminology of their favourite topic to

their hearts' content, tailored exactly to their needs.

And let's say, for this English chat, the Slovenians would charge each other €30 per hour, like this one in Ptuj.

Alternatively, Slovenians can insist the Complainant

joins them as they sit around in a bar all day, and show off their English in

addition to getting all the above for free, or a beer.

Next, suppose there is the same service for English learners of Slovene,

operating in the reverse direction, also worth a notional €30 per hour.

According to my difficult foreign customer requirements, the Slovene lessons are

not going to be in a bar, so teacher can drink, or outside in the sun, so that

teacher can chain smoke. Or inside with smoke. Interrupting your Slovene

teacher's addictions is a big part of the battle. [80]

In my helpful vision of their strategy there will be books, which are both not

entirely in Slovene, neither too childish, nor too dry and advanced, and very

lavishly illustrated; a blackboard and/or screen, perhaps a video or audio

language laboratory, teachers who are unwavering in their own consistency about

Slovene, and who are actually language teachers and not someone else who has

been co-opted to fill this unusual role, above all a COURSE PLAN, and all the other things which are impossible

"because it's Slovenia". That's what they say, meaning it's a bit crap.

In June 2022, €30 is roughly five hours' minimum wage in Slovenia for a student,

3.2% of the national monthly minimum wage, and 7.5% of the single unemployed

welfare rate.

The ZRSZ stated 180 hours to Slovene level A1 would be €9600 which is €53.33 per

hour. Six levels pro rata would be €57,600, 61 months of minimum wage or 143

monthly single person welfare allowances. The devoted student with no need for

earned income, food, heating or accommodation could be a master of the language

in just 12 years.

Thirdly, we hypothesize that for one hour which may last 45 minutes, neither

party is particularly enthusiastic about spending €30 for the other's services.

Both, after all, have something the other wants, and the overheads in talking

for a living are low.

Teaching aids cost more, which is why Slovenia never has any.

Prevented by ZJRS 14, the Englishman can't legally charge anything for his side

of the bargain anyway. His chances of employment are "near zero"

€30 is therefore more precious to the Englishman than the Slovenian.

But being in the most likely place to hear Slovene, things are at least asymmetrical in his favour, he imagines.

Finally, to complete our visualisation, an English person, in Ptuj, wants a Slovenian person to teach him Slovene at the level he needs to be at, just as the Slovenian needs the English person to test him at the level he is at.

Now we

are ready for our teaching experiment to commence.

The hospitable Slovenian host begins, speaking in Slovene. And so, after one

hour of speaking Slovene and explaining in English, or by pointing, the

Slovenian has given away €30 worth of educative value.

But all the time, in the same hour that this is going on, while the Slovenian

has this foreigner there, a quiet tragedy is taking place.

What is this melancholy undertow? Though the foreigner is in his grasp, the

Slovenian is not saving €30 on free English practice.

The Slovenian, based on the expectations to which he is habituated, feels that €30 of educative value has been lost in this time.

Not the hypothetical €30 he didn't get paid for the Slovene

lesson, but the other hypothetical €30 he would have saved on his English.

Much of the Slovene lesson will have been conducted in English.

The teacher may try to claw something back by

turning the language lesson into an interrogation about things he wants to know,

including any fishing around for personal details about the foreigner to be

shared around, for village reputational purposes.

Why do that? In a hick town with four translators, a fifth could mean 20% less

work each. Worse than that, I would be better at the destination language

English.

Consequently the people with the most experience of teaching Slovene (entirely unsuccessfully as far as the Complainant can see) are the very ones with the most to lose by doing so. It does not take long to find something to pin on the invader.

This loss they may rue every second, which in our €30 example is worth 0.83 of a

cent. For Slovene is a commonplace for them, needing no explanation.

Why, they are asking internally, does the foreigner want or need their language

anyway, when he has the useful one? It's suspicious, for sure.

This is Slovenia's best excuse for its humdrum amdram performance, compared to the

Disney spectacular promised by ZJRS 13.

Whereas, the genuine English is a rarity, at least in the boondocks.

Recalling the third experimental condition, their time with this gratis mobile

language laboratory is precious.

In the Complainant, by contrast, they see a life of ease. For it must be,

according to lore and the Law, that this type of foreigner has no need of an

income.

He has a bigger language and comes from a bigger country. For the convenience of

the supplicant, everything is assumed to be adequate.

Any contrary events are seen merely as a further

source of possibly interesting language material, not real problems requiring a

solution. Indeed from the free English student's perspective the longer and more

complicated the foreigner's problems, the better.

If the pressure to actually reveal something which might stop Slovenia messing

up the Complainant's life gets too intense, it is time to remind the teacher he

really should learn Slovene, and how long has he been here etc., and cut and

run.

Even if they do not know exactly how, or anything of their anti-foreigner laws

and administrative practices, the Slovenian is certain the English foreigner

must surely be basking in the wealth of a ripened nationality.

This is Slovenia's topsy turvy racial category error, of which only the lost

island of Doctor Moreau could conceive.

Since the self-employment prospects of the marginalized victims of Slovenia's

introverted language teaching performance are "near zero" by law, Slovenia's

characterisation of them as a wealthy elite could hardly be wider of the mark.

If they have any money, they didn't get it here.

But look: minus €30 for the unpaid Slovene teaching, minus the €30 value of the

hour wasted not getting the unpaid-for real English...speaking his own language

in an instructive way has led to a total conceptual minus for our poor Slovenian

of €60.

And with a racially rich category of person, just

to add salt to the wound!

Hence "The Sixty Euro Problem".

Even if they charge you €30 for the Slovene they only break even.

Consequently the exchanges always gravitate quickly Englishwards. Slovenians are

indoctrinated in school to treat encounters with native speakers as a resource.

"Ask questions" they are taught. And they do. The same questions. Over and over

and over again. And the same people ask the same foreigners the same questions

over again too. The winners are:

Slovenians are endlessly presented with the foreign failures of their own master

plan. In a bleak economic landscape except statistically their adaptation to an

imaginary €30 gain is a difficult habit to break. A notional €60 loss is

unthinkable; their hospitality is thus unbreakable.

Semi-successful Slovene is greeted with distrust, mixed with concern about the

potential lost magic free foreign value. Of course the learner's attempts may be

very tedious for the listener.

The necessarily English elaborations of structural topics bear little

resemblance to the way the native acquired the language as a child, who has no

knowledge of grammar, but a corpus around him or her to imitate.

On top of that, Anglophones would be forcing Slovenians to supply something they

instinctively or superstitiously believe you do not want.

Whereas every conversation, every interaction which succumbs to the lure of

English, is attached to a €30 note. A €30 imaginary gain is better than a €60

imaginary loss every time.

Despite this, the hospitality is real, at least in the hearty mind of the

hospitalier. But it is on a budget. His offer is ten times too low.

The Complainant could not pay the gas bills with a "sit down and have a beer!" or a

"come and join us!". Smiles proved non-fungible at the supermarket checkout.

If only they were willing to pay for the knowledge they definitely think the

wise foreigner ought to have for them, while they audit your noises.

With this carefree cash-free arrangement you can show off to your friends that

you have "got" a foreigner.

If being had were a viable currency, Anglophones could survive indefinitely in Slovenia. It isn't. [80]